He exits his house into the garage. Clamps adorn the walls. “You can never have too many clamps; A lot of clamps. Some woodwork shops will have a wall of clamps, all types, and sizes.” This is where the magic happens!

Steve Petermann knows his tools. He worked for engineering companies for about 40 years, retiring at 62, the earliest age he was eligible for benefits. Now 66, he spends days in his garage turned woodwork shop.

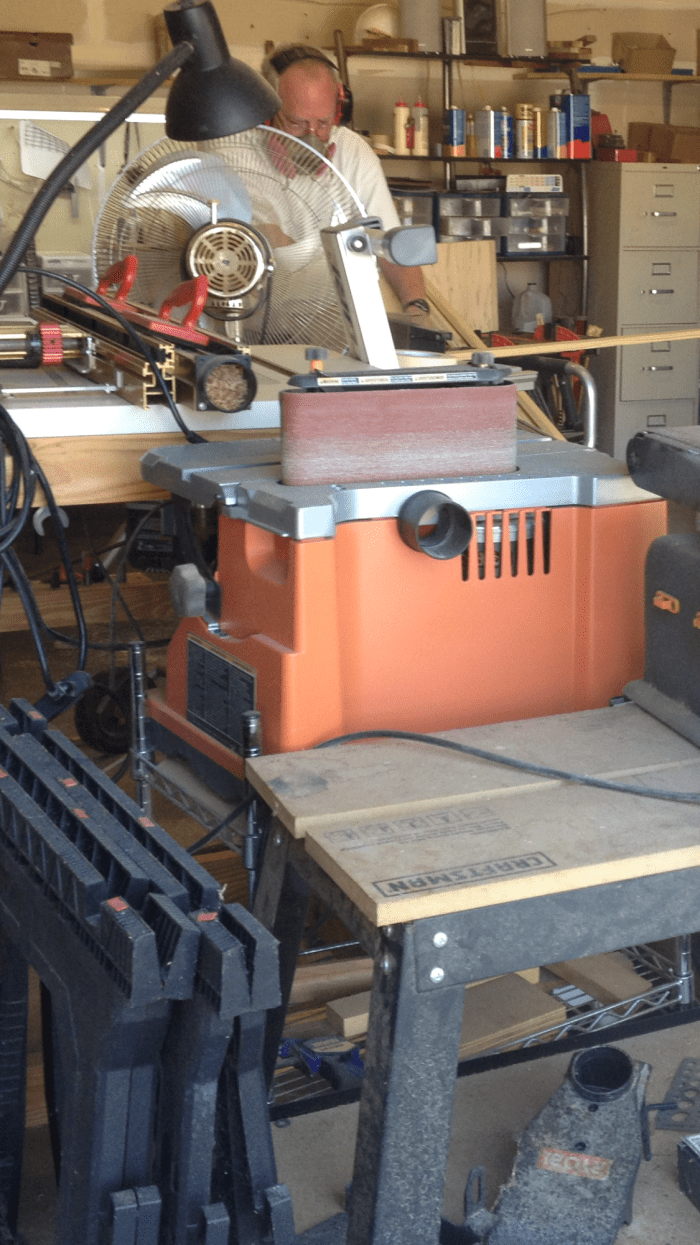

There is no scarcity of cutting tools in the shop. The drill press with a vice that holds workpieces together is perched next to a router table, used to round off and make holes in wood, not far from the spindle sander and two saws, all electrical. Sawdust covers most of the floor, and the whiff from stains occasionally compromise the air quality. A movable rotating fan blows the still air to offset the smell.

This two-car garage opens up in the front of his house. It not only provides proper ventilation but affords much needed natural light, depending on the season. Some overhead lighting sheds additional illumination on the ample workspace. In the event of an imminent storm, his woodwork tools on wheels, are easily rolled to the side to make space for his van, parked in the driveway, used to transport materials for his newly-found vocation.

His smooth hands, spared from any cuts from the saw are scar-free. His dad, an experienced woodworker, one time, split his finger by half an inch. Blades now have sensors, saw stops they are called. Rule of thumb, his thumb still intact, never put your hand close to a cutting edge.

Growing up, there were no jokes in his home. Later, he found out his dad had a great sense of humor, but because his mom would not stand being teased, that part of their life was money under the mattress, hidden.

Today, Petermann spends three hours a day making Native American flutes. He was already making bows, Archery Bows, when a girlfriend started flute lessons, so he too bought a flute and began playing. On occasion, he is on staycation- rides his bicycle, plays tennis, goes fishing or golfing.

Flutes are very expensive. At least, the type he plays can set you back $250, so he bought the equipment to make them himself. He hands me one he made two weeks earlier to see. It is slender, feels sturdy and is well-polished.

Cornell Kinderknecht playing Steve Petermann’s flutes.

He read everything he could about flutes. “So, I read everything I could,” he says, “everything,” he repeats, seated at his computer in the garage, arms folded across his chest, bending over closer as if to whisper in my ear.

Not having a teacher, the computer is his master. Having an engineering background comes in handy in making flutes as they must be designed right in the first place. Steve, an introvert by his admission, uses his time alone to make flutes. Over an extended period, his consistent execution of this practice helped the transition from an engineer to the art of flute making. One of his flutes played a solo in Carnegie Hall.

Engineering entails designs, as does flute making. Flute, a woodwind instrument is about physics. There is a waveform based on air pressure, frequency, and temperature. Every sound has a spectrum of frequencies in it. In the key of A, for example, the fundamental frequency oscillates at 400 cycles per second.

To begin, he picks a key, an A, enters the Router diameter and other dimensions for the sound hole and other configurations on a spreadsheet. The computer calculates the diameter of the flute, length, and thickness of the sound hole and bore depth.

He dons a mask, plugs his ears, grabs the uncut pieces of wood, cuts them and planes to size as accurately as he can. He makes them long enough for the correct key.

He then moves on to make channels in the wood. Using his design sheet, he selects the right router bit. With the router table set up, he cuts the channels in there, a semi-circle cut. This process is not rushed because wood particularly will chip.

He starts routing. As it gets close, he checks the wall thickness with a dial indicator to give the flute a consistent thickness. He cleans up the bores with sandpaper. Next, he mills the sound hole between the main bore and the slow air chamber.

Placing a piece a time at a 45-degree angle in a jig, a wooden frame he had put together for this purpose, he chisels to knock some unwanted pieces off, ending the roughing out process before smoothing everything out.

He finds the edges of the bores, marks them as a guide, lines them up, and then glues them together. But to get good adhesion, he roughens the fixed surfaces first.

Using tissue paper, he cleans the bored-out holes and the sides of any excess glue. “You want to put enough glue. If you overdo it, then you wipe some off. Just make sure you have enough coverage,” he says.

At this point, the shape is not round but square-looking. So he runs it through the joiner to get the desired shape. He then develops the body and the mouthpiece, using a round over router bit. “What I am trying to do is get a nice round shape here,” he says, sanding it down with the sander.

He makes the flute longer than it ends up being, so he would later cut the end to the desired length. Now he readies it for tuning

With his iPhone tuner, he tunes the flute. Plays a song on the flute, blows into it, to see if it matches that on the iPhone. If it does not, he makes some adjustments on the holes till it does. If the pitch is sharp, he applies clear fingernail polish inside the hole.

Looking at the finished product, he makes a connection to his flute making process. Here he draws upon the lore of another musical instrument – the making of organ pipes.

“I also read about organ pipes because they are similar.”

Are all these fancy tools necessary to make a small flute? I wonder aloud. “You can make a whistle without power tools. The Native Americans did it using the end of the arrow to gouge a hole out. You know the Anasazi Indians out of New Mexico, they make rim-blown flutes, which are hard to play.’

To demonstrate, he sips water from a cup sitting next to his keyboard, to moisten his lips for playing, picks up an empty milk gallon, holds it to the edge of his lips and blows across it. It sounds like his flute.

His choice of wood is relatively soft. He mostly uses aromatic cedar. He brings the flute closer to my nose to get the smell of the wood.

“Cherry is also excellent. It is not toxic. Dust can be toxic. Almost any wood is toxic to some extent.” Well, he certainly knows which wood is toxic.

“Cocobolo is a real beautiful dense wood, but it will do a number on you. It can cause lung disease if you are not careful.”

Steve was married for 15 years, but they grew apart. He knew the marriage was over after they went for counseling and the priest asked that they be totally honest. His wife said she could not.

“I will marry again but here are the conditions,” Steve says. “She has to be single of course, wants to get married immediately, should have no relatives, should be terminally ill and must be rich.”

His dad, a fighter pilot, stationed in Italy, flew a dive bomber in 1942. He was a brave guy. “One time his plane got shot up in the air, so he returns to base, gets on another plane and takes off to catch up with the rest of his squad. He gets shot again, returns to base again and gets back up there to dogfight,” he remembers.

“Yeah, I miss my dad. It would be three years since he died.” He watched his mother and father die. “They laid there and died and in a matter of seconds, their skin color changed,“ he says. He confesses holding imaginary conversations with his dead dad thinking of things his dad used to do when he was alive.

When he is not making flutes, he fills the rest of his time learning Spanish. “You’ve got to do something with your day,” he says.

“When you are working, you do nine or ten hours a day if you consider driving to and from work. That’s 50 hours a week you got to fill in with something. You can’t play golf every day,” he says.

He learns 35 new words every week, hoping to know 2,500 words by year’s end. He then utters a sentence in Spanish, laughing as he speaks,“tu eres feo ,” he says, you are ugly.

Then he for the only time in our conversation asks me a question: “Why did you not ask me why am I so handsome?’ To which I replied, you are just as ugly as me.

PS: Steve Petermann is my neighbor and best friend. He has over a dozen patents in engineering still in use today.